If you’ve ever tried to match a bolt to a nut and felt that frustrating “it almost fits” moment, the culprit is usually thread pitch. Thread pitch is the spacing of the spiral ridges on a screw or bolt, and it’s the number that decides whether two threaded parts will mate smoothly or grind, jam, and damage each other. Once you understand thread pitch in both metric and imperial systems, fastener selection stops being trial-and-error and becomes a quick, reliable check you can do in minutes.

This guide explains thread pitch from the ground up, shows you how to measure it accurately, and helps you avoid the classic beginner mistakes—especially the common trap of mixing metric and imperial threads that look similar at a glance.

What is thread pitch?

Thread pitch describes how far apart the threads are. For most everyday fasteners, it can be thought of as the “spacing” from one thread crest to the next along the screw’s length.

In the metric system, thread pitch is measured directly in millimeters (mm). A designation such as M10 × 1.5 means the bolt is about 10 mm in diameter and the thread pitch is 1.5 mm. That “1.5” is the distance between one thread and the next. Many metric thread references also note that if the pitch isn’t explicitly written after the diameter, it often implies a default coarse pitch series depending on the standard being used.

In the imperial/Unified system, thread spacing is most commonly expressed as threads per inch (TPI). A designation such as 1/4–20 UNC means the bolt is 1/4 inch in diameter and there are 20 threads in one inch of length, with “UNC” indicating a coarse series in the Unified system. A current overview of Unified Inch Screw Threads standardization and designation is associated with ASME B1.1 references.

If you want a one-sentence definition you can remember: thread pitch is the thread spacing—measured in millimeters for metric fasteners and described as threads-per-inch for imperial fasteners.

Why thread pitch matters more than you think

Diameter is what people notice first, but thread pitch is what makes parts compatible. Two bolts can look the same thickness and still be completely incompatible if their pitch differs. This is especially true in metric sizes where the same diameter may exist in multiple pitches, such as an M10 bolt that might be M10 × 1.5 (coarse) or M10 × 1.25 (fine), depending on the application and standard series. Documents and charts derived from ISO preferred combinations exist precisely to standardize which diameter-and-pitch pairings are common and recommended.

The practical risk is cross-threading. When the pitch is close but not identical, a bolt can sometimes start threading, giving you false confidence. Then it tightens abruptly, feels gritty, and cuts into the mating threads. Once that happens, even the correct fastener may no longer fit cleanly.

Metric thread pitch made simple

Metric threads are typically written in the pattern M diameter × pitch, like M8 × 1.25 or M6 × 1.0. That pitch is in millimeters, which makes measuring and verifying straightforward once you get used to it.

A detail that helps beginners is understanding the idea of “default” metric pitches. Some references explain that if you only see “M8” without an explicit pitch, it may imply a standard coarse pitch under the default assumption described in related ISO thread systems (depending on context and the referenced standard). That’s useful shorthand, but it’s not beginner-proof. When buying replacements or specifying parts, it’s safer to use the full designation.

Imperial threads and the role of TPI

Imperial threads usually communicate spacing through TPI. The higher the TPI number, the closer together the threads are. That’s why a 1/4–28 thread is “finer” than a 1/4–20 thread: the same inch is divided into more threads.

You’ll also see series labels like UNC (coarse) and UNF (fine), which are common Unified series categories discussed alongside ASME B1.1 references and the way Unified threads are designated in practice.

Thread pitch vs thread lead: a quick clarity check

Beginners sometimes hear “pitch” and “lead” used interchangeably. For most bolts and screws you’ll handle, they are effectively the same because the threads are single-start. In single-start threads, one full turn advances the screw by one pitch.

Where it differs is in multi-start threads, where the screw advances by more than one pitch per revolution because there are multiple intertwined thread “starts.” This is more common in specialized mechanisms than in everyday bolts, but it explains why two screws can look similar yet travel different distances per turn.

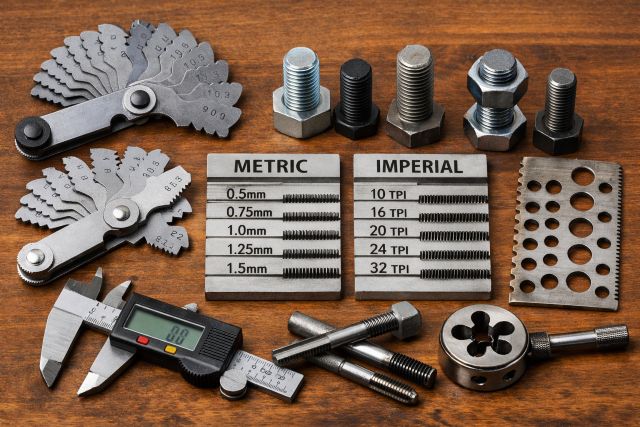

How to measure thread pitch accurately

The easiest path is a thread pitch gauge, because it is designed for this exact problem. You match the gauge leaf to the thread shape until it nests perfectly into the grooves, then read the pitch (metric) or TPI (imperial). If you do any regular DIY, maintenance, plumbing, or mechanical work, a pitch gauge quickly pays for itself in saved time and avoided mistakes.

If you don’t have a gauge, calipers and a ruler still work well with a simple technique: measure across a known number of threads, then divide to estimate. One engineering how-to explains using a caliper to measure from the crest of the first thread to the crest of the tenth thread as a workable approximation method when a gauge isn’t available.

For metric threads, this becomes very natural because your result is in millimeters. If you measure the distance over ten thread intervals and divide by ten, you’re directly estimating pitch in mm.

For imperial threads, you can count how many threads occur in one inch. If you only have a metric ruler, you can still do this accurately by measuring 25.4 mm and counting threads in that length, since the inch-to-mm relationship is exact. NIST documents the internationally agreed definition that one inch is exactly 25.4 mm.

Convert thread pitch between metric and imperial

Conversion is where “almost fits” problems often reveal themselves. The reason is that metric pitch and TPI are inverses of each other when expressed in the same length unit.

Because 1 inch equals exactly 25.4 mm, the conversion is clean and dependable. NIST’s length standards page explains the exact equivalence in the context of the international yard and inch definition.

To convert TPI to metric pitch in mm, divide 25.4 by the TPI value. To convert metric pitch in mm to TPI, divide 25.4 by the pitch.

A classic example is 20 TPI, which corresponds to 25.4 ÷ 20 = 1.27 mm pitch. That number is important because it explains a very common beginner trap: a 1.25 mm metric pitch can feel “close” to 20 TPI, but it isn’t the same. That closeness is exactly why mismatches sometimes start threading and then jam.

If you want to sanity-check your math, general unit conversion references also state the same exact inch-to-mm relationship, which reinforces that 25.4 is not an approximation.

The biggest beginner mistake: forcing a close match

Most thread damage happens because people apply torque too early. A correct match will typically spin on by hand with minimal resistance for multiple turns. If it binds quickly, that’s your signal to stop and re-check pitch.

This matters even more when mixing systems. A metric bolt and an imperial nut can be close in diameter, and some pitches can be numerically close once converted, but “close” still ruins threads. When you’re not sure, measuring is faster than repairing.

Coarse vs fine threads: what you should choose as a beginner

Coarse threads tend to be more forgiving in everyday conditions. They generally tolerate minor dirt, paint, or small dings better than fine threads and are easier to start without perfect alignment. Fine threads can feel smoother and can be useful where design specifications call for them, but they can be less forgiving if you’re threading at an angle or dealing with worn parts.

The most practical approach is to match what the equipment or product originally used. If the original bolt was a fine series, replace it with the same pitch. If it was coarse, stick with coarse. For imperial hardware, this commonly aligns with UNC versus UNF series conventions described in Unified thread standard contexts.

Understanding thread standards without getting overwhelmed

You don’t need to memorize standards to benefit from them, but it helps to know what names you’re seeing on charts and product pages.

Metric thread sizing and preferred combinations are commonly referenced through ISO standards such as ISO 261, which is used as a basis for many “metric thread chart” resources. Some industry references explicitly mention that ISO 261 specifies preferred diameter-and-pitch combinations, while related standards provide selected subsets and dimensional details.

For imperial, the Unified system and ASME B1.1 references are commonly cited when describing how thread form and designation work. If you’re purchasing bolts labeled UNC or UNF, you’re in that ecosystem.

Real-world scenarios where thread pitch knowledge saves you time

Imagine you’re replacing a missing bolt on a machine guard. You find a bolt that looks right, but it tightens after half a turn. Without thread pitch awareness, the temptation is to grab a wrench. With thread pitch awareness, you pause, measure, and notice the pitch doesn’t match. That one minute prevents permanent damage to the threaded hole.

Consider another scenario: you’re assembling imported furniture and you’ve got a pile of “spare” screws from older projects. A screw that looks similar may be the wrong pitch, especially if one set is metric and the other is imperial. Knowing that the inch is exactly 25.4 mm and using the pitch conversion quickly tells you whether you’re close-but-wrong.

Or think about 3D printing and threaded inserts. Printed holes often need a specific insert size, and the insert expects a matching pitch screw. When you choose a screw by diameter alone, it may appear to fit but still fail because the pitch doesn’t match the insert’s internal thread.

FAQ: Thread pitch questions beginners ask

What is thread pitch in simple words?

Thread pitch is the spacing of screw threads. In metric fasteners it’s the distance between threads in millimeters, and in imperial fasteners it’s usually described by how many threads fit in one inch (TPI).

How do I tell whether a bolt is metric or imperial?

Start with measurement. If the diameter reads cleanly in millimeters and the pitch matches common metric values, it’s likely metric. If the diameter aligns with inch fractions and the spacing is best described as a whole-number TPI like 20 or 24, it’s likely imperial. Thread measurement guides also recommend using a caliper and pitch gauge for reliable identification rather than guessing by eye.

How do I convert TPI to mm pitch?

Use the relationship based on the exact inch definition: pitch in mm equals 25.4 divided by the TPI value. This is reliable because the inch is defined as exactly 25.4 mm.

Why does a bolt start threading and then jam?

This is a classic sign of a pitch mismatch, especially when mixing metric and imperial parts or mixing coarse and fine series at the same diameter. It can also happen if threads are dirty or damaged, but the “starts easily then binds quickly” pattern is often pitch-related.

Is 1.25 mm pitch basically the same as 20 TPI?

They are close, but not the same. 20 TPI converts to 1.27 mm pitch using the exact 25.4 mm per inch relationship. That small difference is enough to cause binding and thread damage.

Conclusion: thread pitch is the fastener skill that prevents costly mistakes

Learning thread pitch pays off immediately. It helps you match bolts and nuts confidently, avoid cross-threading, and move between metric pitch (mm) and imperial TPI without guesswork. When you’re unsure, measure first, convert using the exact 25.4 mm-per-inch relationship, and only tighten after the parts thread smoothly by hand. That one habit prevents most thread damage and makes every repair, build, or replacement feel dramatically easier.