A vapour control layer (often shortened to VCL) is one of those building details that feels small on paper but makes a huge difference to real-world performance. When it’s placed correctly and detailed properly, it helps prevent hidden condensation, mould growth, and timber decay. When it’s placed in the wrong location, or left full of gaps, it can do the opposite by trapping moisture inside the structure.

In this article you’ll learn exactly where a vapour control layer goes in walls, roofs, and floors, how it differs from a breather membrane, why “warm side placement” is usually the safest default, and how to avoid the common mistakes that cause condensation problems. You’ll also get practical, jobsite-friendly guidance you can apply whether you’re building new or upgrading an existing envelope.

What a vapour control layer is and why it matters

A vapour control layer is a layer in the building envelope designed to reduce water vapour movement by diffusion from the warm, humid interior toward colder parts of the construction where moisture can condense. In simple terms, it helps keep indoor water vapour from drifting into the places it can do damage.

It’s important to understand that diffusion is only one way moisture moves. Another pathway is air movement through gaps, cracks, and penetrations. Many building science sources emphasise that air leakage can transport far more moisture than diffusion, sometimes by very large multiples, depending on conditions. That’s why the best-performing buildings don’t treat a VCL as “just a sheet”; they treat it as part of a continuous strategy that also controls air leakage.

This is also why the details matter. A VCL that’s perfectly placed but poorly sealed around sockets, downlights, pipe penetrations, and junctions may not deliver the moisture control you expect.

Vapour control layer vs vapour barrier vs breather membrane

People often use these terms interchangeably, but they do different jobs.

A vapour control layer reduces vapour diffusion. A vapour barrier is usually more vapour-tight and blocks diffusion more aggressively. That can be useful in some roof and cold-climate assemblies, but it can also be risky if it prevents the structure from drying when it inevitably gets damp.

A breather membrane, by contrast, usually sits on the outside of the insulation zone and is designed to resist wind-driven rain while allowing water vapour to pass outward so the assembly can dry. Many roof and wall systems rely on this outward drying potential, especially when the inside layer is vapour-controlling.

If you remember one distinction, make it this: the VCL is typically an internal layer that reduces vapour flow from inside to outside, while a breather membrane is typically an external layer that supports drying to the outside while protecting against weather.

The “warm side” rule and what it really means

You’ll frequently hear the guidance that a vapour control layer should be placed on the warm side of the insulation. In many common building scenarios, that rule is a reliable starting point. The reasoning is straightforward: you want to stop warm, moisture-laden indoor air from reaching colder surfaces within the build-up where it could reach dew point and condense.

UK moisture management guidance and roof build-up recommendations commonly describe an air and vapour control layer on the warm side of insulation in relevant roof constructions, reflecting this general principle.

However, “warm side” isn’t a magical universal position. Buildings don’t experience one static set of conditions. Heating seasons, cooling seasons, and daily humidity swings can change vapour drive direction. Assemblies with substantial external insulation may keep the structure warm enough that the condensation risk shifts. Air-conditioned buildings in hot-humid climates can reverse the usual assumptions, pushing moisture inward. Climate-specific guidance from authoritative sources shows that vapour retarder needs and placement can vary by climate zone and assembly type.

A good designer keeps the warm-side rule as a baseline, then checks whether the assembly has a safe drying path in the real climate and operating conditions.

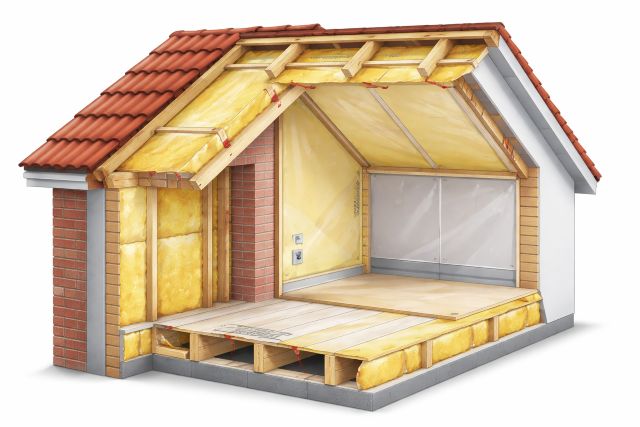

Vapour control layer placement in walls

Timber frame walls with insulation between studs

In a typical timber frame wall where insulation sits between studs and the outside face includes sheathing plus a weather-resistive layer, the vapour control layer usually belongs on the room side of the insulation. In practice, that often means it is installed behind plasterboard or integrated into a membrane system that also serves as part of the airtight layer.

This placement helps limit the amount of moisture reaching the colder side of the wall where the sheathing and outer layers can sit at lower temperatures during winter. It’s a well-established approach in many heating-dominated or mixed climates, and it aligns with the general “warm-side vapour control” principle used across roof and wall guidance.

A realistic example is a family home where a bathroom or kitchen sits on an external wall. Those rooms produce frequent humidity spikes. If the vapour control layer is on the warm side and properly sealed, diffusion is reduced and incidental moisture is managed more safely. If, instead, the layer is missing or leaky, moisture can migrate into the wall and condense on colder surfaces, particularly during cold spells.

Walls with continuous external insulation

When you move insulation to the outside of the structural layer, the temperature profile of the wall changes. The sheathing or structural layer becomes warmer, which generally reduces the risk of condensation occurring on that plane. In such assemblies, an internal vapour control layer may still be used, particularly as part of an airtightness strategy, but the level of vapour tightness required can be different from a traditional stud-only insulated wall.

Some building science guidance explains how exterior insulation can keep condensing surfaces warmer and shift the dew-point risk outward, which is one reason continuous insulation is often praised for moisture robustness as well as energy performance.

The practical point is not that vapour control becomes “irrelevant,” but that the assembly can become more forgiving. You still want good airtightness and thoughtful vapour control, but you’re less likely to create a cold moisture trap behind internal insulation.

Masonry walls with internal wall insulation

Internal wall insulation on masonry, particularly on older solid walls, is one of the highest-risk scenarios for hidden condensation because it can make the original wall colder. In many internal wall insulation details, the vapour control layer is placed on the room side of the insulation, again following the warm-side principle, and it must be detailed carefully around junctions.

This is where “good enough” detailing often fails. A small gap at a skirting line or a poorly sealed service penetration can funnel humid indoor air behind the insulation where it meets a cold masonry surface. If you’re working on internal wall insulation in older buildings, it’s wise to treat the project as moisture engineering, not just insulation installation. Where budgets allow, hygrothermal modelling is sometimes used for risk checking in sensitive retrofits.

Vapour control layer placement in roofs

Roofs are less forgiving than walls because roof structures often see colder external conditions and have less capacity to buffer moisture. This is why roof moisture guidance frequently emphasises the importance of a continuous air and vapour control layer on the warm side of insulation in many roof build-ups.

Pitched roofs with insulation at ceiling level

In a traditional ventilated loft, insulation usually sits at ceiling level with a cold loft space above. Here, the vapour control layer belongs at the ceiling plane, on the warm side of the insulation. The aim is to reduce the amount of indoor moisture entering the loft space where it can condense on cold timbers and roof underlay.

In practice, many homes rely on the ceiling finish and careful sealing at penetrations, but the risk increases as homes become more airtight and more insulated. A well-considered VCL strategy combined with excellent air sealing at loft hatches, downlights, and service penetrations can make the difference between a dry loft and one that accumulates moisture in winter.

Pitched roofs with insulation at rafter level

In a warm pitched roof or room-in-roof design, insulation runs along the rafters so the attic space stays within the thermal envelope. In these assemblies, the vapour control layer typically goes on the internal side of the rafter insulation, again on the warm side. The outside layers frequently support outward drying, often via vapour-permeable roof underlays, depending on the system and manufacturer guidance.

This arrangement fits the broader warm-side principle referenced in roof moisture guidance and helps reduce moisture reaching colder roof layers.

Flat roofs and why vapour control is critical

Flat roofs deserve special attention because they are notorious for condensation issues when detailed incorrectly. A common modern approach is the warm deck flat roof where the vapour control layer is installed on the warm side and is sealed continuously. Above it sit the insulation and the waterproofing system. This configuration is often used because it keeps the deck and structural elements warmer, reducing condensation risk.

Guidance documents discussing roof moisture management highlight the importance of correct warm-side AVCL installation and warn about risks when vapour control and airtightness are not treated as continuous layers.

Cold deck flat roofs, where insulation is below the deck and a cold void exists above, rely heavily on correct ventilation and careful moisture control. Many modern guidance discussions are cautious about cold deck flat roof performance unless ventilation and detailing are robust.

If you want a single practical rule for flat roofs, it is this: treat the vapour control layer as a precision-installed, fully sealed internal layer. A loosely draped sheet with unsealed laps and penetrations is an invitation for warm moist air to find its way into the roof build-up.

Vapour control layer placement in floors

Floors introduce another moisture source: the ground. That’s why floor moisture control often includes membranes that are not exactly the same thing as an internal vapour control layer.

Suspended timber floors over vented voids

In suspended timber floors above a ventilated void, you typically want the vapour control layer on the warm side if it’s being used as part of the internal airtightness line. That often means placing it above the insulation layer, depending on the build-up. The key is to maintain continuity with the wall airtightness line, because junction leaks can drive significant moisture movement via air flow.

If the void below is damp, the strategy may also include a separate ground vapour barrier on the soil to reduce moisture entering the void. That layer is doing a different job than an internal VCL, and confusing the two can lead to poor outcomes.

Ground-bearing slabs

For concrete slabs on ground, the critical moisture layer is usually the damp-proof membrane system intended to block ground moisture. This isn’t typically described as a “vapour control layer” in the same way as a wall or roof VCL, but it performs a related moisture-blocking function. A common real-world issue arises when moisture-sensitive finishes are installed before the slab has dried sufficiently, effectively trapping construction moisture. In that scenario, fixing the timeline and verifying slab moisture can be more effective than simply adding another layer on top.

Airtightness and detailing: what makes a vapour control layer succeed

The biggest difference between a vapour control layer that works in theory and one that works in a building is continuity. Moisture problems often start at the weak points: edges, junctions, and penetrations.

Building science references consistently stress that air movement can carry far more moisture than diffusion, which is why sealing is not a “nice to have.” It is fundamental to moisture safety.

The most common leakage points are service penetrations such as electrical back boxes, recessed lights, duct and pipe penetrations, and poorly sealed junctions at floor-to-wall and wall-to-roof transitions. A robust approach is to plan a service zone so the vapour control layer is not repeatedly punctured, and to use compatible tapes and grommets designed for membrane sealing rather than generic tapes.

Another practical lesson is that sealing overlaps alone is not enough. The edges where the membrane meets masonry, timber, or window and door frames are often where continuity is lost. Detailing those transitions with compatible sealants and tapes is usually more important than the brand name of the membrane itself.

Common mistakes that cause condensation and mould

One of the most damaging mistakes is placing the vapour control layer on the cold side of insulation. This can trap moisture inside the assembly because the layer blocks drying in the direction the assembly needs. Even if the assembly seems “dry” at installation, buildings get wet through minor leaks, construction moisture, and seasonal humidity. A cold-side vapour-tight layer can turn a small wetting event into a long-term moisture problem.

Another common mistake is confusing a breather membrane with a vapour control layer. A breather membrane is typically meant to sit outward and allow vapour to pass through for drying, while a VCL is usually inward to control vapour drive from inside. Mixing these roles can remove the assembly’s ability to dry.

A third mistake is assuming that diffusion control is the main moisture battle. In many real buildings, air leakage dominates moisture transport, so the VCL must be detailed as part of a continuous airtight layer to perform as intended.

FAQs about vapour control layers

What is a vapour control layer?

A vapour control layer is a layer that reduces water vapour diffusion from the interior into colder parts of the building envelope, lowering the risk of interstitial condensation and moisture-related damage.

Does a vapour control layer always go on the warm side?

In many common wall and roof assemblies, placing the vapour control layer on the warm side of insulation is a reliable default. However, climate, air conditioning, and the ratio of external to internal insulation can change drying behaviour and influence the best approach. Climate-zone guidance from reputable sources shows that vapour retarder requirements can vary by region and assembly.

Is a vapour control layer the same as an air barrier?

Not necessarily. A vapour control layer is intended to control diffusion, while an air barrier controls air leakage. Some membranes can serve both roles if they are fully sealed and continuous. This matters because air leakage can transport far more moisture than diffusion in many situations, so treating the layer as airtight is often essential for moisture performance.

Where does the vapour control layer go in a flat roof?

In many warm deck flat roof constructions, the vapour control layer is installed on the warm side beneath the insulation and is sealed continuously to reduce the risk of interstitial condensation. Roof moisture guidance highlights the importance of correct AVCL positioning and continuity for performance.

Conclusion: Vapour control layer placement is simple, but the detailing is where projects win or fail

A vapour control layer is most effective when it is placed to support the building’s moisture flow and drying potential rather than trapping moisture. In many standard wall and roof assemblies, that means installing it on the warm side of insulation, keeping it continuous, and detailing it like a serious airtight layer. Roof moisture guidance commonly reinforces warm-side AVCL strategies in appropriate build-ups, particularly where condensation risk is significant.

The most important practical lesson is that location alone is not enough. Because air leakage can move much more moisture than diffusion, continuity at junctions and penetrations often determines whether the envelope stays dry.